From 1978 until 2014, I worked in a New York City agency responsible for providing affordable housing to low-income residents. The housing stock I managed and provided to low-income tenants became city-owned as a result of landlords walking away from dilapidated properties they could no longer afford to own. When landlords abandoned their occupied properties, that meant tenants and supers were left to their own devices to provide essential services like electricity, water, hot water, heat, repair leaks, clear stoppages, and making cosmetic repairs such painting, plastering, and repairing locks and windows.

Tenants in abandoned buildings also provided their own security to prevent drug dealers and/or squatters from breaking into vacant apartments and basements, as well as to prevent thieves from stealing heating systems, fuel, and pipes throughout the buildings. One would think, with all the problems, that tenants would run away from their buildings just as their landlords had done. Most tenants would have left if they’d had someplace better to go. But where to go was the question and the dilemma.

When I first started collecting information to write this workplace memoir, I did it because it helped ease my anger. I felt so helpless and hopeless as I tried to improve tenants’ living conditions. I’d make a repair here and something else there would fall apart. When I asked the suits and “stuporvisors” for help, I’d get looks of disbelief or outright refusals. I thought I’d go crazy the first year I worked for the city. I didn’t understand the system or its language and how to use it correctly. By the second year, I’d learned the appropriate lingo and how to apply it, as well as the games people played within the system. By the third year on the job, I’d finally learned how to manipulate the system to help me. I’d learned how to go around it if I had to and still make it work for me.

I felt a burning need to write a tell-all book to expose all the horrid events I’d experienced while trying to improve peoples’ lives. I thought, I’ll show those sons of suits how to do things right. I’ll expose all the ills within system that chewed up new, idealistic managers like me and spit them out like so much waste product. Now the ball was in my court. I was going to force the system to change because I was going to expose its dirty, uncaring, racist underbelly.

Then a funny thing happened. The longer I worked the job and didn’t allow the job to work me, I began to enjoy my newfound knowledge and the power it gave me to get things done. Exposing my agency’s wrongdoings didn’t seem nearly as important as getting work done that actually improved living conditions for tenants. I realized it was far more important to write about a job that was changing so rapidly, I was afraid I might be obsolete within the next year or so.

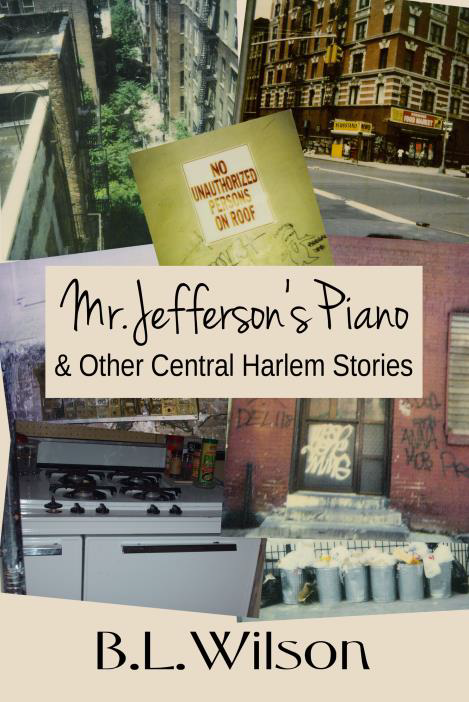

When one of my favorite role models died, I felt a deep urge to put my fingers to the keyboard and write what I experienced as a newly minted NYC property manager until I retired thirty-plus years later. I felt if I didn’t write about the job I did fulfilling my duties as a NYC real property manager, nobody would. As a result, I wrote Mr. Jefferson’s Piano & Other Central Harlem Stories.

Why I wrote: Mr. Jefferson’s Piano & Other Central Harlem Stories

My novel is a workplace memoir that weaves together a rich tapestry of 68 short stories, agency memos, and letters of events that take place during the late seventies, eighties, and nineties as seen through Melba Farris’ eyes. Melba writes notes about everything work-related, chronicling her journey into the field of property management as she tries to help her less fortunate brothers and sisters with their housing woes.

She meets the oldest woman in Harlem in the title story Mr. Jefferson’s Piano. 101-year-old Nora Jefferson and her kid sister, 96-year old Minnie, enchant her with the story of how their father acquired the baby grand that sits in the middle of their living room.

Melba becomes an exorcist when a routine housing complaint about a broken stove turns into removing an invisible devil from Ms. Johns’ oven in The Devil Made Me Do It.

In Neisha, Melba writes a series of memos to her boss asking for help to improve the hazardous living conditions of seventeen-year-old Neisha, an independent minor, her two young children, and a teenage brother—all of whom Neisha is responsible for since her mother died of AIDS.

These three tales represent some of the delightfully funny, sometimes perplexing, but intriguing personalities the author encountered during twenty-five years as a property manager performing her job duties in city-owned buildings.

The links are below for Mr. Jefferson’s Piano & Other Central Harlem Stories:

Amazon Kindle: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B01KTTJYVM

Amazon Kindle UK: http://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B01KTTJYVM

Amazon Kindle CA: http://www.amazon.ca/gp/product/B01KTTJYVM

Createspace: https://www.createspace.com/6465691

Smashwords: https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/659566

Book trailer: https://youtu.be/hiQj8jzE_3c

Connect with BL Wilson at these links:

Blog: http://wilsonbluez.com

Facebook Business Page: https://www.facebook.com/patchworkbluezpress

Goodreads: http://bit.ly/1BDmrjJ

Linked-in: http://linkd.in/1ui0iRu

Twitter: http://bit.ly/11fAPxR

Smashwords profile page: http://bit.ly/1sUKQYP

Amazon’s Author Page: http://bit.ly/1tY3e27